What Does Kafala Mean?

The term Kafala means ‘Sponsorship’ in Arabic. The Kafala system is a sponsorship system for migrant workers in Lebanon, as well as several other Arab countries, which governs migrant workers’ immigration, employment, residency and personal status in the country.

Lebanon’s government ministries do not provide any oversight or governance on the migrant domestic workers’ (MDWs) lives once they arrive. Rather, the Ministry of Labour and the Ministry of Interior just provide minimal regulations for recruitment agencies for the MDWs’ entry permits. They generally remain minimally involved in all matters relating to the MDWs’ rights, wellbeing and status. The few rights MDWs do have are administered through their work contract and the Labour Arbitration Councils.

The responsibility for all matters relating to the MDWs fall under the purview of the sponsors, who are also the employers of the MDWs. The sponsors/employers have unchecked power over the MDWs’ lives in regards to their legal status, employment, health care, accommodation and private lives. This essentially gives impunity to employers to confiscate their passports, overwork them, deny their wages, deprive them of food and reasonable sleeping conditions and inflict physical and sexual abuse. In addition, the Kafala system does not allow for the workers to change jobs or leave the country without the employers’ consent.

In short, the Kafala system is an exploitative system that gives employers tremendous and often-abused power over migrant women who work, sleep and eat in the homes of these same employers.

Who Are The Migrant Domestic Workers?

MDWs in Lebanon are most commonly young women from South-East Asian and Sub-Saharan African countries, such as Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, The Philippines, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, Cameroon, Ghana and Gambia.

They come from diverse religious, ethnic, and linguistic backgrounds. Many are from rural areas, while others are recruited from the cities. The majority of these women are often responsible for providing for their families, such as their parents, siblings or children.

They leave their respective countries in pursuit for better economic opportunities, through the pretence of safe migration pathways. Instead, they have fallen into the trap of the Kafala system, and are now subject to human trafficking, violence and labour exploitation.

Why Are Migrant Domestic Workers Travelling to Lebanon?

Many MDWs travel to Lebanon to work for their own financial stability, to fund their higher education, or to send remittances as the sole providers for their parents or children.

However, MDWs are often lured by recruitment agencies in their countries through false advertisements and promises regarding potential living and work conditions in Lebanon. In many cases, the misinformation and deception is so significantly exaggerated that the process is classified as human trafficking. However, there are also cases where the women are aware of the subpar conditions but still agreed to the offer due to their destitute situation.

MWA believes that governments from countries of origin have failed to sufficiently raise awareness about the dangers of the Kafala system, resulting in the MDWs’ limited understanding of the severity of human rights abuses and dangers that entail the Kafala system.

What Human Rights Abuses and Risks Do Migrant Domestic Workers Face?

Before even arriving in Lebanon, many MDWs are exploited by being pushed into debt in order to pay for costly recruitment fees, which can go as high as 1500 USD. In many countries it is illegal for the recruiters to charge these recruitment fees to the workers, but they are imposed regardless, and often collected through intimidation or force.

In other cases where recruitment agencies demand a lower fee, the recruitment agents make an illegal arrangement where the MDW is expected to work up to three months without any salary to repay the debt.

Upon their arrival in Lebanon, they immediately experience a violation in their freedom of movement, with their passports being confiscated by General Security at the airport, who then hand over the passport to the sponsors/employers rather than the workers themselves. This immediately delineates the imbalance of power, with the MDW being completely dependent on their sponsor/employer. The moment a sponsor (i.e. Kafeel) ends his sponsorship for his/her employee, the MDW is deemed an illegal resident without any rights, legal status or freedom to leave. The power of the sponsor/employer reaches as far as total control over the MDWs’ choice regarding employment. MDWs cannot change their jobs without explicit permission from their sponsor/employer. If a worker escapes, they can be considered as “absconders” and are at risk of either further exploitation on the streets of Lebanon, or subject to detention and deportation.

The system enables labour exploitation through low wages (~ 150$ per month) or wage theft.

The labour exploitation and lack of oversight and regulation, allow sponsors/employers to force their employees to work under extreme conditions such as extensive hours up to 18h a day as well as unsafe and unhealthy work with lack of adequate protective equipment.

In addition, MDWs have limited access to health care, education and public services due to the control employers/sponsors have over their lives.

The Kafala system is building on racial and sexist stereotypes as well as capitalist and patriarchal structures, which enable the physical, verbal, sexual and emotional abuse of MDWs perpetuated by their employers, local service providers, neighbours and society in general. A persisting culture of impunity has normalised this violence to the extent that abusers will not even realise or admit their own wrongdoing.

Who Profits From The Kafala System?

The Kafala system in its complexity and through its exploitation is lucrative for various actors, taking advantage of the MDWs vulnerability and dependence.

Among the main profiteers are the recruitment agencies, which, both in the sending country as well as Lebanon, receive large sums of money through recruitment fees from both the MDWs’ as employees and the sponsors as employers. These payments are usually justified as fees for paperwork, visa applications, permit fees and flights , but have been proven to be priced way higher than their actual costs

Since the Kafala system in some cases uses methods akin to human trafficking, including illegal emigration from sending countries, forging of fake identity papers,cross-border smuggling, different forms of coercion and deceipt, reports have shown that, particularly in Central African countries, transnational organised criminal groups also benefit from their links with recruitment agencies.

The sponsors/employers are evidently the main profiteers of the Kafala system since the MDWs labour is much cheaper than the local labour force including the payment of taxes and fees for employees. Since the economic crisis has severely affected the Lebanese financial sector, the exploitation and wage theft against MDWs has increased manifold, with employers often using the currency crisis as an excuse to either underpay or not pay the workers at all. Since 2019, MDWs increasingly find themselves in situations of forced labour and modern-day slavery unable to fight for their rights due to the exclusion from the Lebanese Labour Law and unable to leave the country due to the lack of money to cover the expenses for travelling.

Finally, both the Lebanese government and the sending countries profit from the Kafala system through the exploitation of the MDWs as a cheap labour force as well as an income source through remittances.

How Does The Kafala System Enable Human Trafficking and Modern-Day Slavery?

The lack of government oversight of recruitment agencies both in the sending countries and in Lebanon has allowed unregistered recruitment agencies to operate freely, using fraudulent and malicious tactics to lure MDWs into agreeing to unfair contracts and recruitment practices, including the payment of unreasonably high recruitment fees up to 1500 USD.There have been countless cases documenting practices of luring and tricking the women into agreeing to the terms of their work based on false promises, fraud and even threats.

The misinformation, power imbalance and false promises for recruitment meet the requirements of the international legal definition of human trafficking according to the UN Palermo Protocol. The implications of MDWs’ residency status being dependent on their sponsor/employer further empowers smugglers and human traffickers in using fraudulent practices for repatriation or to further re-traffick the women to a different country with the Kafala system.

The exclusion of MDWs from Lebanese Labour Law exposes them to exploitation, servitude and abuse, which constitutes a contemporary form of slavery.

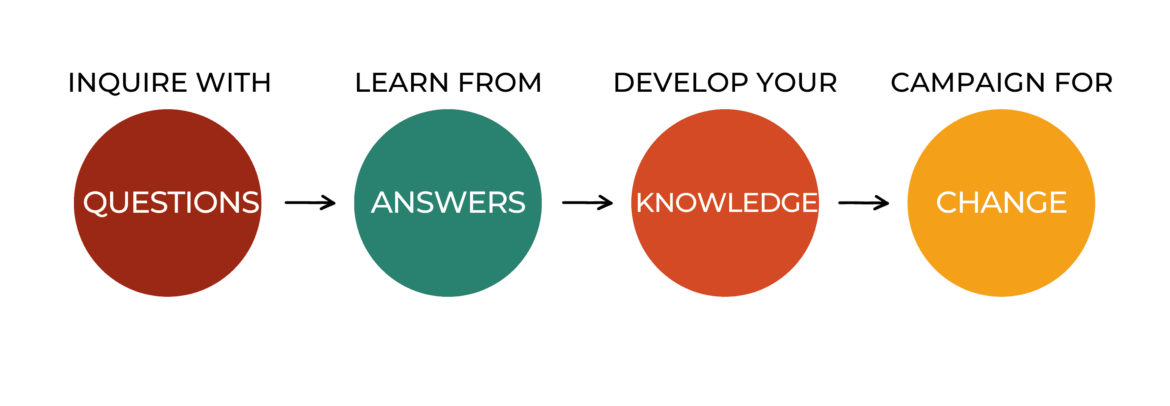

What Needs To Change?

Following campaigning and advocacy efforts, some countries including Qatar and Saudi Arabia, have implemented some reforms to the Kafala system. To this day however, Lebanon has failed to abolish the Kafala system or reform it.

Sustainable change towards a fair and just system for MDWs is only possible if the Kafala system is completely abolished and replaced by an immigration and labour system under governmental regulation and with adherence to international human rights standards.

Visa and work permits should be regulated by the respective Lebanese ministries, with possible work of regulated and monitored recruitment agencies with official licences.

Employers should no longer sponsor the MDWs permits and residencies and only work with fair and standardised contracts that guarantee the MDWs rights and freedoms.

In order to ensure the adherence to international legal standards as well as to enable MDWs to unionise, organise and campaign for their own rights, MDWs should be included in the Lebanese Labour Law as well as the protection of other laws in Lebanon.

Perpetrators of violence and abuse should be held accountable and MDWs who have experienced violations in their rights and freedoms should receive justice including reparations.

The Lebanese government should introduce a general amnesty for all MDWs who overstayed their residencies in Lebanon to accommodate MDWs that were forced to remain and work in Lebanon without official permits and residency.

For lasting and genuine change, the Lebanese government should proactively tackle racist stereotypes and narratives in its own society through campaigns, awareness-raising and educational programs