Everyone in life has a role model. We all have that one person we look up to because they exude confidence and strength. One of my greatest role models is my mother. In honour of Lebanese Mother’s day, I interviewed my mother, who has worked in Lebanon for about 30 years. She came to Lebanon in 1992 as a migrant domestic worker with the hopes of getting a better opportunity to provide for her younger brothers. She, along with her two sisters, sacrificed to put her younger brothers to go to school and then eventually college. She was a pioneer and warrior but even soldiers have moments of weakness and defeat. I remember once when I was 13 years old, I saw her sitting at the bottom of the stairs in the kitchen and contemplating on life. She was silently grieving. She saw me then let out a cry “I am a terrible mother, because I am not able to raise my own children. My daughter sleeps from home to home and I have to send you to a boys’ home in order to keep my job.”

My mother came to Lebanon under the Kafala system. It is a broken immigration and labour system. The system was structured in a way that the laws being placed didn't ensure a worker’s security, but it gave a margin for a lot of exploitation to happen. My mother lived at her boss’ home and had a “room” in the kitchen (which is a small attic with a bathroom). She worked from Monday to Saturday afternoon and was paid a mediocre salary.

My mother had a desire to leave a legacy and have her own family and she had me a few years later. At the time of my birth it was uncommon for domestic workers to have a family. The work conditions forced migrant mothers to go home, give birth and let their child be raised by a family member while they provided financial support. My mother hid her pregnancy in fear of losing her job and did a lot of hard labour. Even though she temporarily lost her job, her boss’ daughter cried and pleaded for my mother to come back. As a premature baby, I had to stay in the hospital for several days after my birth and my mother’s boss decided to cover the fees. However, she refused to let me be raised by my mother because she thought I was a hindrance to my mother’s job and I only stayed with her for two months then started sleeping at her friends’ homes. I saw her on the “weekends” and we continued this routine until I was sent to my residential boys’ home where I saw her once a month . She challenged the system because she believed in her motherhood.

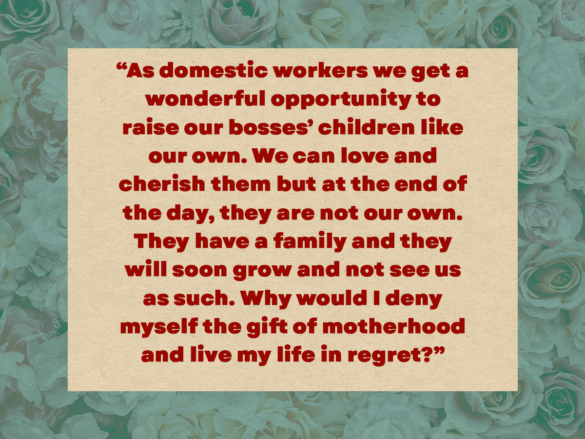

A few years later my mother had my little sister and multiple people were outraged by the fact she was having another child in the same work conditions. Once a fellow domestic worker asked her why she decided to have another child, my mother responded, “As domestic workers we get a wonderful opportunity to raise our bosses’ children like our own. We can love and cherish them but at the end of the day, they are not our own. They have a family and they will soon grow and not see us as such. Why would I deny myself the gift of motherhood and live my life in regret?”

In my mother’s 30 years of employment in Lebanon, she gained a lot of wisdom. She believes that domestic workers are workers with dignity and should be treated with respect and not as an object. She said that women are seen in multiple careers from business owners to merchants and they all get the opportunity to be mothers. Their children should have the opportunity to live with their families and be given rights as well as Lebanese nationality. While many Lebanese people enjoy that luxury in the Ivory Coast, many domestic workers’ children will never have this opportunity. My mother is an active member in multiple nonprofit organisations in hopes of a better future for domestic workers and their families. She concluded the interview saying “ no one can take away my motherhood because I have the right to be a mother.”

Ochienga - Son of a Migrant Domestic Worker in Lebanon